“I have never forgotten Singapore. Singapore is

- Johnny in Johnny Bikin Filem

It is well-known that Singapore (then part of British Malaya) is where Malay cinema first took root with the film, Leila Majnun (Love-struck Leila), directed by B.S. Rajhans in 1934. Rajhans was among the bevy of directors brought in by Shaw Brothers & later, Cathay-Keris. Among them were directors from Indonesia, the Philippines & Hong Kong. The industry boomed after the war & thence throughout the 1950s & 1960s.

These were interesting - & turbulent - times. The worldwide socialist movement was making its influence felt among literary writers, journalists & left-wing activists. Hollywood cinema was moving away from classical to social-realist oriented films with films like On the Waterfront, The Wild One & East of Eden, among others (and which also included film noir). These films cast their influence not only on the filmmakers in Singapore but also on society at large. Elements depicted in these film surface in Johnny Bikin Filem (Johnny Directs a Movie - JBF), one of the great ‘unseen’ Malaysian films, which exists in 2 versions & has a fascinating, complex & chequered production history.

JBF was directed by Anuar Nor Arai, a lecturer with Universiti Malaya at the time. He had attained his PhD in Film & Theatre from the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Upon his return to Malaysia, he became an Associate Professor teaching film in the Dept of Media Studies at the University of Malaya. A prolific writer of film & theatre scripts, he had a library of more than 70 completed scripts, but misfortune dogged his career right up to his death. His scripts were largely rejected or overlooked; a few were produced as feature-length telemovies or made into a couple of TV episodes helmed by other directors & also himself. I sent 2 of his feature film scripts, Putera Merdeka (on Tunku Abd Rahman) & Kuala Lumpur Aku Punya (a musical), to Finas on his behalf but a reply was not forthcoming nor even an acknowledgement.

In 1994, Anuar proposed to University Malaya the making of a feature film in which film students would work alongside professional actors & a film crew so as to better understand film production all the way from script to screen. Prof Hamid Bakar, the Head of the Dept fully supported the idea & so about RM700,000 was allocated for the purpose. This was probably the most positive thing (& perhaps the only one) that happened to Anuar throughout his life as a (would-be) filmmaker & writer. And perhaps Prof Hamid was the only person in a responsible position to ever have had faith in him.

The production of JBF began in June of 1994 with locations in Penang, Perak, Selangor & KL. The film was shot on 35mm film & was finally completed in 1995 but only up to the ‘double-head’ stage, i.e. with the sound track & the visuals separated. A film is only considered completed when picture & sound are ‘married’ & made into a check print & thence into release prints for distribution & exhibition. With the absence of a professional production manager, Anuar had overshot scenes & subsequently, overspent the budget. He applied for more funds, which were not forthcoming & so he began to use his own money. The processing, editing & sound services were done on credit. In the end, the production costs for the first 5-hour film school version of JBF came to about RM800,000.

The film brought together student actors, Zack Idris (Johnny), Hamsan Mohamad (Joe), Monica Chan (Ani) & Linda Lee (Sara), with professional actors, M. Amin (Shariff Sutero), Erma Fatima (Siti Rapeah), Wafa Abd Kadir (Siti Kamaliah), Jalaludin Hassan (Mastar), Abu Bakar Omar (Pak Hitam), Suzaidi Saidin (Yusof Telo), Izie Yahaya (Robert) & J D Khalid (Pak Ayob). M Amin was a veteran actor & director of films in Singapore in the 1960s.

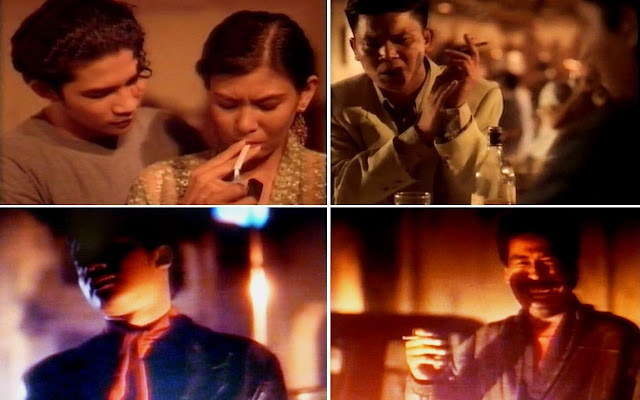

JBF was a story about gangsters set in the cabarets, alleyways & docks of 1950s Singapore. Amongst all of Anuar’s stories, JBF is the most autobiographical & is, in its background story, about the Malaysian film industry & of Anuar’s desire to transform it into a real cinema. The film begins with a black screen & Anuar’s voice calling the shots. The first visual is of a clapperboard depicting Anuar’s shooting of JBF. This is followed by the shooting of a love scene which reeks of bad acting & inane dialogue, a signifier of the kind of films being produced in Malaysia (then & today). After the director’s credits, a montage introduces the main characters in the story & their milieu of cabarets, alleyways, dilapidated buildings & grimy docks. Visuals of Johnny on a train heading for Singapore is intercut with these scenes. After having a sexual liaison with Sara, the owner of a Malay opera troupe (bangsawan), Johnny is offered to work at the Shaw Brothers film studio. At the signing of the contract, Johnny shoots dead the owner, signaling his aggressive entry into the Chinese-owned industry to do things his own way. He then teams up with an opera director, Shariff Sutero, to direct a film that he will produce.

In between, Johnny has trysts with 3 other women – one, a cabaret dancer, Ani; then Siti Rapeah, a singer who will become an actress, & finally he ties the knot with a Malay opera primadonna, Siti Kamaliah. Sexual tensions come to the fore as Johnny seems to be too preoccupied with trying to save bangsawan & the making of films. He also violently duels with Mastar, the leader of a group of gangsters & kills him. He is now acknowledged as a godfather among the gangsters as well as the film people. He is confronted by a young Chinese producer who threatens him & leaves after giving a knife cut to Johnny’s face.

But there are other hidden forces that Johnny has set into motion. At the end of the story, Johnny enters a set while shooting is in progress. The director orders him out but he keeps returning, signifying his unhappiness that things were still being done as in the earlier days. It is then that a shot rings out & Johnny drops dead. A quick cut reveals 2 shadowy figures on a building, one of them holding a rifle. Earlier, the Chinese producer showed his unhappiness by boldly coming face to face with Johnny. But who, in reality, were these killers who were hiding in the shadows? Anuar leaves the question hanging. The architecture of the building is an indicator as to who they really are. (In later years, other filmmakers like Mansor Puteh, Nasir Jani, U-Wei HajiSaari, Dain Said, Chris Chong, Yeo Joon Han & Mamat Khalid have alluded to the same ideas in their films.)

Anuar was also the art director for JBF. His understanding of narrative structure, the visual look, lighting, costuming, setting, decor & symbolism puts JBF in a class of its own in Malaysian Cinema that would be difficult to surpass. Anuar’s references came from Hollywood movies. The signifiers can be seen in the portraits of Hollywood stars of the 1950s such as James Dean on the walls of the cabaret. This is contrasted with Johnny’s house where his ‘Malayness’ is reflected in the portraits of Malay nationalists & Malay film stars.

Anuar’s approach was expressionistic with props and gothic lighting playing a symbolic role. Anuar’s overall directing style bordered on the poetic & the lyrical. The visual look of the film was based on chiaroscuro lighting as found in film noir & surrealism. Lighting for close shots referenced Rembrandt’s portraits, that is, with the subjects & backgrounds usually fading into the darkness. Many scenes were in the gothic mode modeled after the visuals in films like Citizen Kane & The Godfather. The setting also referenced Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront with its docks & pigeons. Anuar brought the same level of expression to his theatre production, Ronggeng Rokiah that was staged at Istana Budaya in 2003 & promoted as ‘noir on stage’. I was involved in the play as the set designer & also had a small acting part playing B N Rao, one of the Indian directors of early films in Singapore.

Ronggeng Rokiah was a segment from JBF where a bangsawan performer is given a role in a film but ends up in a traumatic stage - because she is illiterate (read: no knowledge about film as seen in the background story). As in JBF, Anuar used white screens with shadow but they only appeared at the beginning of the play and were used to signify that Ronggeng Rokiah was, in reality, about the film industry in Malaysia & how it did not reflect traditional Malay values like working together & helping each other out (a criticism of industry players). Instead, there was backbiting, stabbing in the back, cheating & conniving. This is reflected in a line of dialogue in the play - & it comes from one of the Chinese gangster characters:

"Cina tipu Melayu, kau dah tengok. Melayu tipu Cina, kita tak takut. Cina tipu Cina itu kau takut. Melayu tipu Melayu itu sudah teruk!" (Chinese cheating the Malays, you have seen. Malays cheating the Chinese, we do not fear. Chinese cheating the Chinese, that you are afraid of. Malays cheating the Malays, now that’s dastardly!)

The final almost 2-hour version of JBF only came about when Mahadi J. Murat, a filmmaker, academic & a friend of Anuar Nor Arai, became a lecturer at the University of Malaya from 1999 to 2006. During his tenure, the university received a bill from Finas for film equipment services for JBF. When Mahadi’s advice was sought, he suggested a way out: get additional funds to finish the film as a cinema feature as well as pay off Finas. The Chairman of the university’s board agreed & about RM200,000 was allocated.

The negatives of the film were at Gaya Lab in Shah Alam, Selangor where they had been processed (with money also being owed to it!). The audio tapes were at Filem Negara where foley recording (creation of sound effects) & some dubbing & sound mixing had been done. Money was also owed to them but there was not enough left to pay them. Mahadi edited the film down to about 2 hours with Anuar supervising, but there was not enough money to properly transfer the sound. Parts of the sound were inaudble & more money was not forthcoming. A voice over narration of M Amin (as Shariff Sutero) was recorded for the opening to reveal the backstory. Scenes were repositioned to make the story as clear as possible.

The approval for the film to go to the cinemas in 2007 lay with the Vice-Chancellor, Dato’ Dr Rafeah Salim. A special screening was arranged at the Asia-Europe Institute. All those attending the screening loved the film but the VC was concerned about the proliferation of images where almost every character was smoking incessantly. She gave orders for the film not to be given a public screening. This 2-hour version was entered for the 2008 Malaysia Film Festival where it won a Best Costume Design award but was never screened to the public. Fate had decreed that Anuar’s 'masterpiece' would never meet with an audience.

Though disappointed, Anuar accepted his fate & that of his one & only cinema feature. His frustrations were alleviated to a certain extent when the film came to the notice of Paolo Bertolin, a programmer of Asian films for the Udine & Venice Film Festivals at the time. I had also made the opening & credit titles for the film – the longest that I had ever done (I'm still owed the balance 50%!). I showed Bertolin a clip of the 2-hour version. He exclaimed in amazement that he had never seen anything like it in Malaysian cinema - & was even more interested when he discovered that there was a 5-hour film school version. A copy with attached English subtitles (by me) was sent to him by Anuar. Unfortunately, Bertolin found a narrative flaw in the film. There was a missing scene crucial to the story. It had not been shot because the professional actress did not turn up for the shoot. Once again, Anuar’s claim to fame eluded him.

In all his scripts, Anuar Nor Arai’s characters face a future that is bleak & lonely. Anuar was aware of this same element in his own life & this became reflected in all his writings. His writings came from his own experiences & setbacks that represented his feelings & frustrations. He went to an early death in 2010 after a brief illness.

Towards the end of JBF, after completing a film as producer, Johnny gives a speech at a reception. Ironically, he says that the film is not yet finished & there is still one more scene to be shot! Art truly reflects life & vice versa. Johnny stands in front of a huge poster of the film & says that he will continue making films. He ends by telling everyone with what looks like a sardonic smile:

"Lepas ini Pak Sutero akan bikin filim, ‘Main Wayang’!"

(After this, Mr. Sutero will direct,’ Making Movies’!).

This was, in truth, Anuar’s own sardonic comment on the industry. “Main wayang” in Malay parlance means to put up a façade or a false front, that is, of not being truthful or sincere. It was aimed at the industry players & bureaucrats who were supposed to help the industry. Anuar also referred to his own culture by using shadows (as in Malay shadow play) in many scenes. He depicted the struggle and trauma of bangsawan actors with their foray into film acting. He depicted a world of shadowy figures alongside the real world. In JBF, he used white screens (signifiers of cinema), that had shadows cast on them. These functioned as negative indexes of the hidden hands at work that were attempting to disrupt or delay Johnny’s (& Anuar’s) efforts to uplift standards of film storytelling.

For those in the Malaysian film industry, “main wayang” is what filmmakers have to put up with. Many things are decided by producers, broadcasters & bureaucrats. Filmmakers have to bite the bullet & go along with them in order to be able to continue making films. The production of alternative films with serious themes would have to be put on hold. The bottom line was all about making money. Films had to sell. But Anuar never compromised in his works. And he paid the price. Johnny Bikin Filem will always be written about but will never be seen. The original 5-hour version will be lost to the audience for which it was lovingly destined for.

Johnny Bikin Filem has many meaningful lines of dialogue that are pointers as to Anuar Nor Arai’s disappointment with the film industry. In a line of dialogue, Johnny says:

"Aku tidak beri kasih sayang aku kepada sesiapa. Kecuali kepada

cita-cita aku yang gelap gelita." (I do not give my love to anyone.

Except to my ambitions that reside in darkness).

And Shariff Sutero says to Johnny: "Singapura tidak beri apa-apa kepada seni." (Singapore does not contribute anything to the arts.)

Malaysia may not have given its love to Anuar Nor Arai nor contributed to the arts in the real sense of the word but Anuar has done it all for his country because of his love & his passion for the arts. His stories were grounded in reality unlike Malaysian cinema which pandered to fantasies & mediocrity. Anuar's destiny was a long drawn-out struggle with unrealised ambitions. His epic hero’s journey, however, is not really a lost cause. It will be an inspiration & guide to other artists like him & will become the stuff of myths & legends in the years to come.

- This is an amended version of an article which appeared in the Singapore Cinematheque Quarterly of June 2013. It also appeared in Daily Seni Online, July 2013. It is included in my book A Guide for Cinephiles & Movie Addicts, 2023 published by Rabak Lit.

Written by: Hassan Abd. Muthalib

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

0 Ulasan